An Altar Called Thank You

Sometimes gratitude whispers for years before it finally finds words. That was the case with my stepdad.

A while back, I wrote a blog post thanking him—not because it was Father’s Day, and not because anyone asked. Just because it was time. Because something in me needed to name what he had been for me.

Here’s what I wrote:

One day, my mom brought home a man who seemed enormous. Over six feet tall, driving a Chevy station wagon that felt like a spaceship to a kid who had only known a one-parent universe.

At the time, I didn’t know how to name it. But something began to shift. He didn’t try to replace anyone. He didn’t make promises or declarations. He just… stayed. Through the slammed doors, the smart mouth, the years when I gave him every reason to walk away, he didn’t.

His name was Warren. He never asked to be anyone’s hero. But as I think about it, he was mine. He passed away a few years ago. And while I told him thank you in a hundred little ways over the years, I don’t know if I ever said all of this. I hope he knew. I think he did.

I’m grateful I had the chance to write those words. But still—there’s always that ache: Did I ever really say it to him? Did he hear the “thank you” in the way I meant it? Did I say it enough?

That’s why this phrase—Thank you—matters so much. It’s one of the four things we’re told to say to someone who’s dying. But I wonder if it’s something we’re meant to say much sooner. Much more often.

In THE PITT, when a father is dying and his adult children are encouraged to speak four parting sentences to him, one of them is simple: Thank you.

Not thank you for being perfect. Not thank you for never letting me down. Instead, it is thank you for what you gave. Thank you for what you tried. Thank you for loving me the best way you knew how.

Dr. Ira Byock, the palliative care physician behind this four-part framework, says that ‘thank you’ is not just etiquette. It’s healing. It allows both the dying and the living to make peace with what’s been, and maybe even with what’s been missing.

But too often, we wait. We assume people know. Or we run out of time.

When I sit with families after a death, they tell stories that glow—memories of kindness. Quiet sacrifices. Everyday grace. You can feel the gratitude woven through the grief.

But I always wonder:

- Did the person they’re remembering ever hear this?

- Did the stepdad know the difference he made?

- Did the teacher ever hear that she changed someone’s life?

- Did the friend know they were someone’s lifeline?

Gratitude lives in our hearts. But it doesn’t always make it to our lips.

Saying thank you isn’t just good manners. It’s soul work. It turns fleeting moments into something lasting. Not just thank you for the big things. But for the faithful, often-forgotten ones:

- Thank you for doing the dishes when I couldn’t get out of bed.

- Thank you for picking me up in that spaceship of a station wagon.

- Thank you for sticking around when you didn’t have to.

These aren’t throwaway lines. They’re bricks in the foundation of love. And when spoken aloud, they build something sacred. These days, I try to say it out loud. On purpose.

To the people who stay. To the ones who hold steady. To the ones who never ask for credit but deserve it anyway.

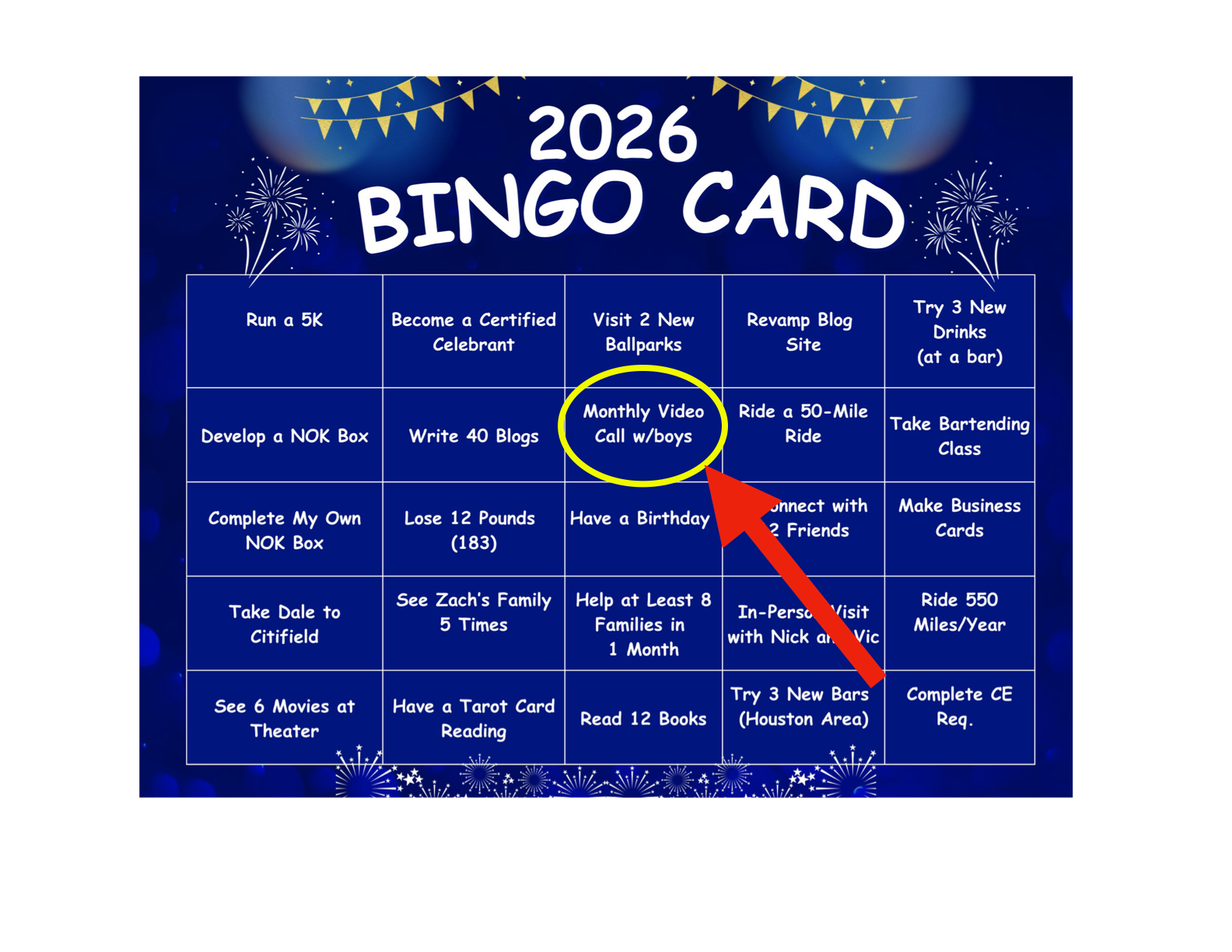

To my boys. To friends. To the stranger who smiles when I most need grace.

Gratitude doesn’t fix everything. But it softens the rough places. It redeems the quiet ones. It builds an altar where we least expect it.

Think of someone you’re quietly grateful for—and tell them.

Not with a grand gesture. Just a text. A phone call. A few words at the kitchen sink.

- Thank you for what you did.

- Thank you for being there.

- I noticed.

- I remember.

Those words don’t just express love. They become an Unlikely Altar.